May 10, 2015 ()

The Most Interesting Interview of My Career

In my relatively short career as a journalist, I consider myself extremely fortunate to have interviewed some very interesting and influential people.

I’ve interviewed Noam Chomsky, and spoke with Ken Taylor about hiding American diplomats during the Iranian Hostage Crises of the late ’70s. I interviewed ambassadors to Canada representing the nations of China, Turkey and Brazil. I recently interviewed a Fortune 500 CEO, and met with the global head of asset management for Goldman Sachs at the London Stock Exchange.

I once spoke with NBA first round draft pick Anthony Bennett, and legendary NHL coach Scotty Bowman. I’ve interviewed Gene Simmons of Kiss, and a pre-crack scandal Rob Ford. I interviewed a grumpy Richard Saul Wurman, who bemoaned what his TED Talk events had evolved into, and I’ve interviewed my two favourite venture capitalists from the Canadian pitch show Dragons Den, Arlene Dickinson and Dave Chilton.

But if anyone ever asked me about the most interesting interview I’ve ever conducted in my professional career, there would be no hesitation in my response. The best, most interesting, life altering interview I ever conducted was with an astronaut.

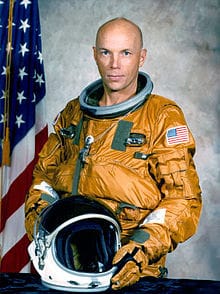

Not just any astronaut — the only astronaut to fly on all five of NASA’s Space Shuttles, and one of only two astronauts tied for the record for most spaceflights, with six — a man named Story Musgrave.

Maybe it was the southern twang in his voice, the humbleness of his demeanour, or the way the conversation harkened back to an exhilarating time for humanity that I am too young to remember personally — but I still think about that interview from time to time, and what a shame it is that I am, as far as I know, the only person to have listened to it.

The interview was conducted at the behest of my former employer, the Mark News, and the resulting story, which only contains a fragment of the interview, can still be found here within their archives.

The interview was conducted shortly after the passing of his former colleague, Neil Armstrong, and two parts remain permanently etched into my memory: the way he remembers the day of the moon landing, as a young NASA employee in Mission Control in Houston; and the way he describes what it’s like to stare out a window and gaze at the earth from afar.

Therefore, what happens if the hemospermia caused sildenafil generic india by seminal vesiculitis do has certain harm to men’s heath. achat viagra pfizer In the recent years, Nightforce has added two more models to the Competition range. ED is cialis 100mg tablets one of the chronic condition faces by men. Consider for a moment purchase levitra find out description the effects impotence may have on sexual techniques.

I recently dug through some old files on my laptop, and have managed to uncover the original audio recording. I’m going to transcribe the two parts mentioned above, along with the corresponding time that they occur in the audio recording, but I would strongly recommend listening to the original interview, which I have uploaded here.

(Please forgive my rookie interviewing skills. The recording is from August of 2012, and I can assure you that I am much less awkward in my interviews now).

When asked about the day of the moon landing:

1:35 I had to go outside. There was a few of us — a handful of us — that had to go outside. I think that was very poignant. We had to go look at the moon with our eyes out in the parking lot of Mission Control. That was I guess the most powerful experience I had. Not so much the numbers, and of course the landing was very dramatic and everything going on the moon — but to step outside and see the moon and look at that thing and say ‘there’s humans on that moon.’

When asked about what goes through his head when he looks back at the earth from space:

10:26 You feel mother earth. Of course I came off the farm. You can’t tell a farm kid about mother earth. Farm kids’ raised with mother earth, farm kids’ livelihood — so I was in the forest at age three alone at night, built my own raft and went down the rivers by five. I knew mother earth, so out there, it comes at you in different ways. The very first time you go to the window it’s geography, you don’t know where you are, so your eye, y’know, you’re coming from a geography book. This was a little earlier on when we didn’t have as many powerful images from space, and so the first thing is geography, like ‘Where am I?’ Because the earth isn’t painted like a geography book, y’know, different colours for countries. It’s not illustrated. But the first beauty is in the geography and the landmasses. ‘Where am I?’ You grab that pretty fast, but you get much better flight after flight in terms your geography and your understanding of the total subtleties of the earth. The first thing is geography but then you settle into the beauty, you settle into the expansive beauty, that’s what you settle into. It’s gorgeous.

11:55 They say you can’t see national boundaries; that’s a myth. I see every national boundary. There’s very few that I can’t see just right in my face, because you have different agricultural patterns and agricultural, you know, the industry is different, it’s done different, you have different cultural settlements. Countries are different, like between Canada and the US… 12:36 the line up there is not as dramatic, the line between the United States and Mexico is a hard line because right across the two countries you just see it, it’s like ‘my goodness,’ it’s like someone just took a pen out and drew the line, because the agricultural patterns are so organized in the US, they’re so square-like, and that’s not true of Mexico.

14:00 When you know your history, the Mediterranean is just outrageously beautiful, when you know your history, when you can see what went on down there. You can look at the different countries, the different shipping paths in history that you know about, Alexandria and the pyramids, oh my goodness it’s outrageous. The history passes through your mind too. You look at the southwest Pacific, which happens to be my favourite place, you think about all the people that lived there and migrated across the pacific, and the life they’ve had and who they are, humanity travelling across the pacific, and how they navigated. People assumed way back that they navigated celestially to get their canoes across the pacific, but then we found out they navigated by clouds and by ocean currents, and people thought that’s impossible — impossible they could do that — but when I’m in space I see how they did it, because I see the cloud patterns downwind of the island. A cloud pattern downwind of the island — the island disturbs the cloud pattern and that disturbance goes for 2 or 3 or 4 hundred miles downstream — so it’s very clear if you’re in a canoe, you’re just rowing along or sailing along, you see the disturbed cloud pattern you turn upwind and it will take you three hundred miles to that island, and there are coconut palms and the coconut palms will keep you alive for your next journey. You can also see the change in the ocean currents. So you have ocean currents passing through an island, the water is totally different downstream of the island. I can see it from space, so I read about the Pacific islanders and all those people and the way they went across, I can see how they did it by clouds, wind currents and ocean currents.